By Jeri Shikuma, Home and Community- Based Programs Administrator

One of our goals at ACC is to enrich the community with topics that are important but sometimes difficult to discuss. Many of us prepare for important life phases like going to school, getting a job, getting married, raising kids, and planning our finances. But how do we prepare for caring for a loved one at the end of his or her life?

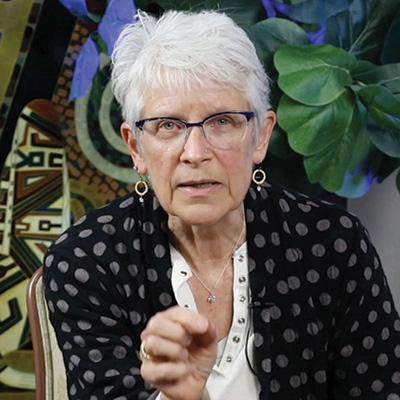

We just completed a four-part workshop series with Julie Interrante on this topic. She is an end-of-life counselor and a former hospital chaplain. Julie is also the author of the book The Power of a Broken Open Heart, Life-Affirming Wisdom from the Dying, available on Amazon.com.

For more than 35 years, Julie has helped family caregivers understand what happens in the final phase of life and how to be present with their loved one. Here are some excerpts from the conversation I had with her after her last talk at ACC

Jeri: In each of your workshops, you had guests talk about caring for their loved ones at end-of-life. Tell us one of these stories.

Julie: I do want to reflect a bit on the couple who lost their adult daughter. Their story offers us the chance to see that each person, regardless of relationship, handles caregiving and grief in their own way. Mark was very clear about the pain and sadness of not being able to protect his daughter from her illness. He showed us through his tears that the experience still touches him deeply. Esta told us how she just couldn’t believe this was happening to her youngest daughter. She also very courageously explained how after her daughter’s death, she and Mark grieved differently. She talked with friends and shared her feelings while Mark was more private and did not have the same community of friends she did. They both shared how they needed to find a time of day that worked for both of them to share their grief together.

Esta and Mark have loved and supported each other and allowed enough room for each to walk their loss in their own way. Letting go of our preconceived ideas about life, love, and loss is the message I hear in their story.

Jeri: We all know that life has many phases, but you identify one called “the completion years of life.” Why do you call it that?

Julie: As I mentioned in the presentation, there is a beginning, a middle and an end to everything in life, including me and you and everyone. For that reason, I think it is helpful to refer to the dying process as life completion because it reminds us that while the timing of our dying or the way we die, may not be in our control, we do take part in our dying. Even if we know our time is short, we can make choices about how we want to live the days or months we do have.

The idea that I am completing my life helps empower me to consciously connect, make meaning, say goodbye, and talk with the people I love about how I want to spend my time and my precious energy. When you share with clarity your thoughts, fears and desires with your loved ones, it helps create connection and gives permission to loved ones to talk openly as well.

How we stay connected in the dying process is the same way we stay connected during the rest of our lives – sharing with honesty, heart, tears, laughter, and presence.

Jeri: Throughout the series you talked about emotions that are normal, but that people may not accept them as such and become disconnected with their loved one.

Julie: It is very normal to have feelings of fear, sadness, relief, uncertainty, and anger to name a few. For many people there is also a feeling of being numb or shut down, sometimes feeling paralyzed. It is not uncommon to have a lack of focus, to lose things, forget names and words that ordinarily come easily. These feelings may be uncomfortable and that is why often people want to get rid of them or don’t talk about them, but they are normal. The feelings we have are providing information about what we need. Taking time to validate our feelings and giving ourselves time and space to express them will enhance our ability to remain connected with the ones we love.

Jeri: When someone’s body is shutting down, certain “normal” things happen, and we have a tendency to want to intervene as opposed to just being present and letting nature take its course. What can people expect?

Julie: I believe you’re referring to the dying process itself. There often comes a time when the person who is dying is no longer interested in eating or drinking. They often lose their appetite and interest in food. This can be disturbing to loved ones because we are used to feeding someone when they are ill. In the dying process however, this is not what is needed. As the body shuts down, we no longer need nor want food and it is important to honor this shift in the body. While this change can be difficult at first, it is signifying that it is time to stop “doing” and to become more present, perhaps simply sitting at the bedside of our loved one. It might be a time to quietly share your favorite memory, or maybe read a favorite poem. This is the time in the process where we receive the gift of being present in this tender, vulnerable and very precious time of life.

Jeri: The caregiving journey doesn’t necessarily end when the care recipient dies. What are some of the important things about the grieving process you would want people to know about?

Julie: The grieving process has a life of its own. Grief is not something we control. It is something we live with. There are a lot of ideas in our world about how grief will or should look, but grieving has many facets and many feelings. Sometimes it looks and/or feels like anger, sometimes numbness. Sometimes grief can look like shutting down. It can look like overeating or crawling under the covers. Sometimes someone in grief weeps for days and weeks on end. Whatever your grief looks like, please honor it. When you are ready, share it.

You can consider a grief support group or grief counseling. When someone we love dies, we are dropped into a very big transition of our own. This is a time of uncertainty. Often that uncertainty includes wondering how you fit in your life now or wondering whether life makes any sense anymore. These are all normal.

There is a general belief that grief will be over in a few weeks or a few months and that after that there is closure. Grief does not work like that. We don’t come to closure. We learn to live with it. Grief is a process, a life process. It is painful, deep, and powerful. It does get better and during it all, you will continue to laugh and love and cry. And you will heal.

Watch Julie Interrante’s four-part end-of-life series at accsv.org/julie. Episodes include:

Conversations in Dying

Creating meaningful Experiences When Time is Limited

Walking a Loved One Home

Life After Loss

Add a Comment